4. Looking back at the income disparity

The Lehman Shock made it very clear that income disparity had been expanding through the 2000s. According to the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare's "Income Redistribution Survey," the Gini coefficient, which measures income inequality (adjusted for the number of household personnel) rose sharply from 0.42 to 0.48 between 2000 and 2013. Around this time in Japan, while real wages were declining, widening disparities were noticeable especially among those with relatively low incomes. In fact, according to the Ministry's "National Life Basic Survey," the percentage of households with a disposable income of less than 3.5 million yen increased by 13 percentage points from 2000 to 2015, and the number of households who answered that they had no savings increased by 7 percentage points.

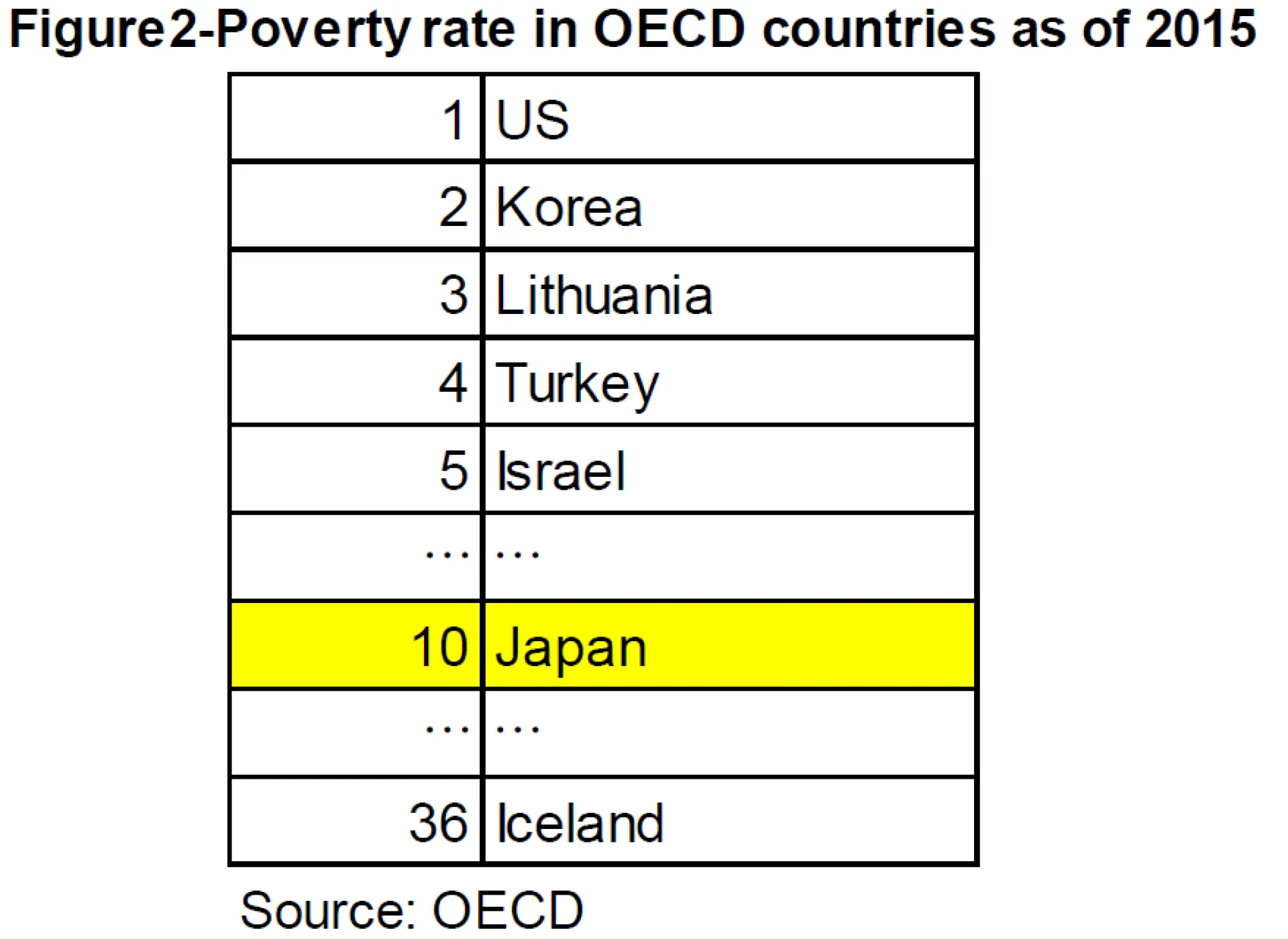

In the United States, the income gap was especially notable amongst the highest income group as the wealthy got wealthier. But in Japan, the income gap widened mainly in the relatively lower income group leading to “poverty among the middle class”. In fact, between 2000 and 2012, the relative “poverty rate,” or proportion of people with less than half the median disposable income, rose from 15.3% to 16.1%. Welfare recipients also remained high at 17% between 2013-2015, or 9 percentage points higher than in 2000. According to an international comparison by the OECD, Japan's relative “poverty rate” was the 10th highest among the 36-member countries as of 2015 (Figure 2). One must look not only at the elderly, but to the emergence of intra-generational disparities among young and middle-aged people. The slogan, "All 100 million Japanese are middle class", quickly began to fade, and the problem of disparity was highlighted. According to the results of the World Values Survey, until 2005,most respondents said that there should be some income disparity to raise motivation. But by 2010, 63% of respondents said that “there should be income equality” and it remains at these levels today. Although employment recovered under Abenomics in the latter half of the 2010’s and income inequality had improved somewhat, the results of these surveys show that widening inequality remains a concern for most people.

5. Correcting disparities which should not impede economic growth

We often hear that correcting income disparity and distribution policies are incompatible with economic growth, and many tend to fall into the argument of choosing between growth and income redistribution. However, the impact of inequality on growth is not uniform. For example, amongst the relatively high-income group, income disparity is an incentive to make one richer, and raising taxes to correct the inequality will merely result in a loss of incentives. On the other hand, for those with relatively low incomes, widening disparities make them aware of their differences with others, work negatively on their motivation, fail to cover sufficient education expenditures, and miss the opportunity to increase their incomes. As a result, it can lead to a hotbed for social unrest and the rise of populism.

Which one is dominant? According to the results of an empirical analysis conducted by OECD staff in member countries after numerous surveys and studies, not only does inequality correction not hinder economic growth, but the redistribution policy among low-income groups in fact promotes growth. In particular, it’s been suggested that investment in education contributes to the subsequent growth potential through the formation and accumulation of human capital.

6. Seeking inclusive growth

The Japanese economy must undergo major changes and transformation in the post-COVID-19 era. Investing in human capital to flexibly adapt to trends and to take the lead is important. It is necessary to focus not only on childhood and adolescence education where you "begin to learn", but also to "re-learn" in your mid and elderly life and recurrent education.

What is required of economic policy is not to counterpose growth strategy with income and distribution policy (For example, investing in education, and boosting support for workers affected by COVID-19.) Rather it is critical that income and distribution policy act to reinforce the growth strategy. This is the aim of "inclusive growth" advocated by the OECD. That is, the realization of an economy and society in which no one is left behind and everyone can live in happiness. I hope that the Suga administration will take an actively promote the "fourth arrow".