Introduction

I am constantly looking out for changes in Japanese society and how they are changing the growth sustainability of Japanese companies. Japan has experienced gradual structural changes, such as an ageing society, economic globalisation and digitisation, and most believed that Japanese society would change slowly over the next 10 to 20 years. However, the dramatic changes in the economic and social environment brought about by COVID have led to an acceleration and we are now seeing cases of Japanese companies transforming rapidly to respond to the new environment. In this report, I would like to consider the potential investment opportunities created by these transformations, with some specific examples.

The background of transformation in Japan

I believe the transformation that is taking place in Japanese companies is undoubtedly a short-term response to the environmental changes brought about by COVID, but it is also due to more medium- to long-term structural changes in their workforce. As a result of generational change, an increasing number of executive managers in Japanese companies are becoming aware of the need for change and are taking more risks.

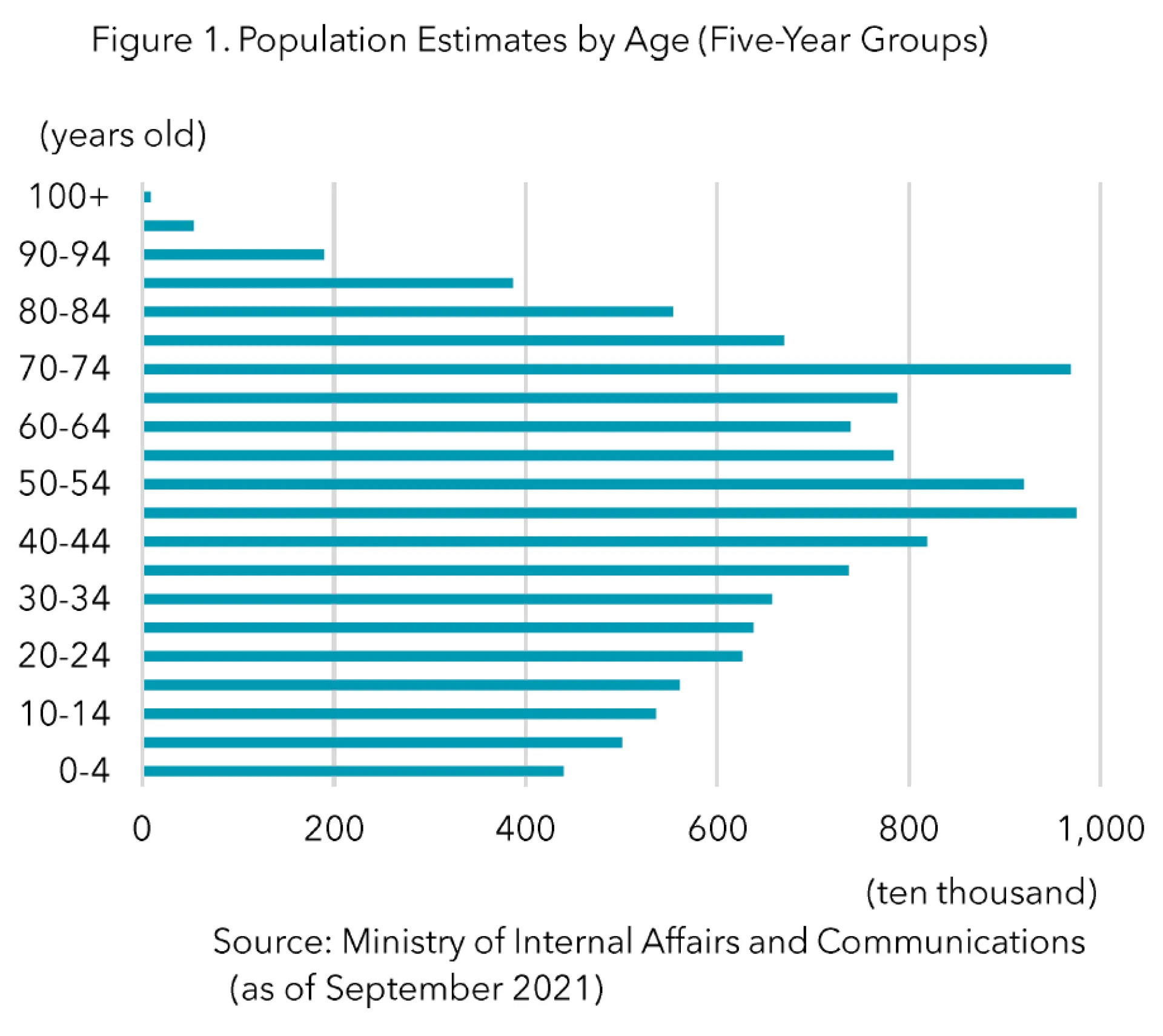

As can be seen from the demographic composition of the Japanese population (Figure 1), the first baby boomers in Japan were those born between 1947 and 1949, immediately after the Second World War. They contributed to the high economic growth of the late 1960s and early 1970s as a young labour force and the bubble economy reached its peak in the late 1980s when they were around 40 years old. During the period when they supported the Japanese economy as a labour force, the performance of companies rose steadily, and they were a generation with a strong sense that hard work would be rewarded. On the other hand, their experience of their own success in the 1980s meant that they were less resilient to change and were unable to cope adequately with the slow growth period of the 1990s and beyond, with globalisation, and with the increasing speed of change brought about by IT since the 2000s.

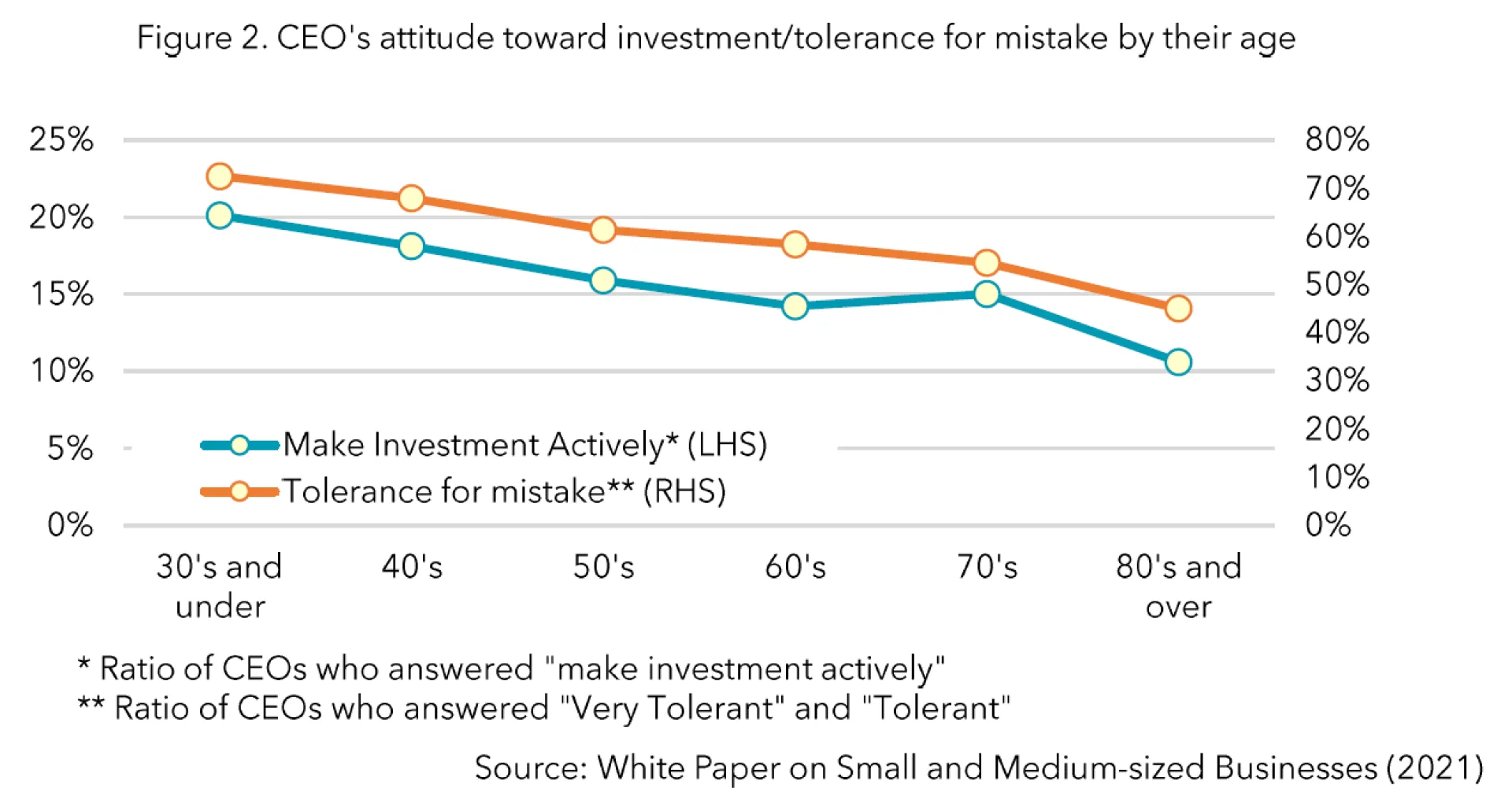

However, over the past decade or so, as they have reached retirement age (generally 65, although many remain on the board until their 70s) and have begun to disappear from companies, I believe signs of transformation are beginning to appear in Japanese companies. The next generation of executive managers who have taken over from the baby-boomers have survived the period of low growth as a labour force, and are therefore more concerned about the current situation and more flexible to change. They are also actively involved in the corporate governance reforms promoted by the Abe administration and are trying to adopt the best practices of Western-style management. A government survey confirms that young business leaders are more aggressive in capital investment and have a higher tolerance for failure (Figure 2). The risk appetite and willingness to change in Japanese companies has increased with generational change.

With such a foundation in place, the recent changes in the internal and external business environment due to COVID have accelerated the transformation of companies. COVID has been a catalyst to carry out the changes that companies already know they need to do but have been avoiding. At the same time, customers have moved away from a traditional attitude of taking excessive service for granted and have become more realistic in their demands within the constraints of non-contact. For example, a large Japanese company had been considering the benefits of remote sales before COVID, but was unable to expand upon it due to the belief that it would create a burden for customers as they would have to print documents. With COVID, however, remote sales quickly became the norm, and sales were soon digitised. In the end, I think that in Japanese society it is surprisingly easy to make a transformation when excuses no longer apply.

This transformation is irreversible and I expect to see further changes in the future. I believe it is difficult to accurately predict the changes that will take place in a year or two, but I also believe that it is not so difficult to imagine what society will be like in 10 or 20 years' time, if we have the right insight.

The transformation of Japanese companies under my focus

Not all listed companies and managers in Japan are changing in this way, of course, and in-depth research is needed to identify companies that can grow sustainably in response to changes in the environment. Currently, I am particularly interested in the following three transformations taking place in Japanese companies, which I see as promising investment opportunities.

The first is "the emergence of businesses using digital platforms". In Japan, as in the rest of the world, the evolution of information technology has made it possible for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) without a solid management base to offer innovative services and products and to develop their businesses.

One company that comes to mind when I hear of companies changing old business practices in Japan with their own digital platforms is M3. Even before COVID, M3 operated a platform that aggregated medical information and provided services to replace the work of medical representatives (MRs). For a long time in Japan, it was normal for MRs to wait in front of consultation rooms to provide information to doctors about medicines. But since the launch of the M3 service, providing information digitally has become the norm, and the service boasts a 90% usage rate by doctors. Generational changes in the digital literacy of doctors, who are their customers, have also helped to drive up usage of this system. In addition, COVID has restricted face-to-face meetings between MRs and doctors, introducing a greater need for this service. M3's goal is not just to replace MRs, but to provide more value-added, data-driven digital marketing. Growth is expected from the expansion of this successful digital business model into China in addition to the further increase in the number of medicines available on their platform in Japan.

On the other hand, Toho is one example of a company that has the potential to grow by leveraging a global platform created by other companies. Toho is an 89-year-old entertainment company that has grown by producing films and animation and showing them in cinemas, predominantly in Japan. However, their sales growth had been low at around 200 billion yen due to a decline in cinema admissions and the diversification of entertainment in Japan. In this environment, the cinema market was badly hit by COVID, and the company made a business decision to rapidly close the distance between itself and video delivery platforms such as Netflix. I believe the company will grow by proactively working to distribute highly competitive animation and other content that has traditionally struggled to be monetised overseas. I think this is another example of the transformations that have been triggered by COVID.

The second investment opportunity I have been looking at is the "globalisation of non-manufacturing industries". In Japan, since the 1990s, a number of manufacturing companies have expanded their production bases into Asia in order to benefit from cheaper labour and reduced foreign exchange risk. Even after Japanese companies lost their competitiveness in final consumer goods such as electrical equipment, the globalisation of the Japanese manufacturing industry progressed, as the competitiveness of advanced production equipment and intermediate goods such as electronic components, was not lost. On the other hand, the non-manufacturing sector has been slow to globalise, despite a sense of tapering off due to Japan's declining population. In Asia, in particular, there is a certain appreciation of Japanese goods and services, but a lack of human resources and management skills to develop globalisation has prevented them from becoming profitable.

One of the companies I have been focusing on is Ryohin Keikaku. Ryohin Keikaku is a retailer that plans, manufactures and sells a wide range of products under the MUJI brand, including high quality clothing, household goods, food and simply designed furniture. The company had continued to grow in sales due to increasing inbound demand in the Asia region and the resulting increase in brand awareness. However, in recent years it became apparent that the company's internal management systems and controls were not keeping pace with the growth, including inefficient inventory management due to a lack of investment in systems. The company was suffering from "growing pains". Traditionally in Japanese companies, CEOs could only be promoted from within the company, and there were cases where people with the same skill set took over management and repeated the same mistakes. However, the company made a business decision to bring in an external CEO, and Mr Domae took over as the CEO in September 2021. Mr Domae had a wealth of experience in consulting at McKinsey & Company, and successfully implemented a systematic retail internal control system at Fast Retailing, known for the UNIQLO brand. The appointment of Mr Domae as CEO is expected to increase the sophistication of the internal control systems to support the company's growth through increased investment in systems and the recruitment of specialist external personnel. I see this as an example of management's willingness to take risks and change.

The third and final opportunity is “digital transformation in the manufacturing sector". Manufacturing is a key industry in Japan and is highly competitive internationally. There are more than 270 products with a global market share of 60% or more, double that of the US. However, a shortage of labour due to the falling birth-rate and ageing population, and a shortage of time due to working style reforms, have become structural problems, and higher productivity has been in demand. In the manufacturing value chain, CAD (Computer Aided Design)/CAE (Computer Aided Engineering) is prevalent in the design process, and machinery is increasingly automated in the manufacturing process. Robots have been introduced in production and e-commerce is widespread in the sales area. However, in the procurement area, there are still many analogue processes such as making paper drawings and requesting quotations by fax, which has been a factor hindering productivity growth.

One company that sees digital transformation in its procurement area as a business opportunity is MISUMI Group. MISUMI had been selling machine parts, tools and consumables to more than 300 thousand companies globally via catalogue and internet sales, but the company was unable to sell complex shaped items through these channels because they could not be standardised. In response, the company developed its own online machine parts procurement service “meviy”, and began offering it in 2016, expanding its scope to include cutting processed products and sheet metal processed products from 2019 with sales of the service continuing to grow rapidly. The service provides online procurement of machine parts that require machining (custom parts), which previously required paper drawings, and offers a series of processes related to the procurement of machine parts online, including transfer by uploading CAD data, AI (Artificial Intelligence)-based quotations, order receipts, manufacturing and shipping. This enables clients to reduce the time they take to source custom parts by an average of 90% and increase their productivity. The supply chain disruption caused by COVID has also provided a tailwind for the widespread use of the service, as it has increased momentum for a review of procurement processes. MISUMI has the top share of the online custom parts procurement services market in Japan, at around 55%, and is expected to grow by expanding this service globally.